|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTE: Click on any image to listen to its audio clip.

Area and Speakers

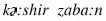

The Kashmiri language is called  or

or  by its native speakers. It is primarily spoken in the Kashmir Valley

of the state of Jammu and Kashmir in India. According to

the 1981 census there are 30,76,398 speakers of the language. The census was not conducted in the year 1991. Keeping in view the

rise of the population over last many years, the current number

of its speakers will be around four million. Kashmiri is also

spoken by Kashmiris settled in other parts of India, and other

countries. The language spoken in and around Srinagar is regarded

as the standard variety. It is used in literature, mass media

and education. by its native speakers. It is primarily spoken in the Kashmir Valley

of the state of Jammu and Kashmir in India. According to

the 1981 census there are 30,76,398 speakers of the language. The census was not conducted in the year 1991. Keeping in view the

rise of the population over last many years, the current number

of its speakers will be around four million. Kashmiri is also

spoken by Kashmiris settled in other parts of India, and other

countries. The language spoken in and around Srinagar is regarded

as the standard variety. It is used in literature, mass media

and education.

Classification and Dialects

There is a general consensus amongst historical linguists that Kashmiri

belongs to the Dardic branch of the Indo-Aryan family. Grierson (1919),

Morgenstierne (1961), Fussman (1972) classify Kashmiri under Dardic group of

Indo-Aryan languages.

The t.mp3 Dardic is stated to be only a geographical convention and

not a linguistic expression. The classification of Kashmiri and

other Dardic languages has been reviewed in some works (Kachru

1969, Strand 1973, Koul and Schmidt 1984) with different

purposes in mind. Kachru points out linguistic characteristics of Kashmiri.

Strand presents his observations on Kafir languages. Koul and Schmidt have

reviewed the literature on the classification of Dardic languages and have

investigated the linguistic characteristics or features of these languages with

special reference of Kashmiri and Shina.

Kashmiri has two types of dialects: (a) Regional dialects and (b) Social

dialects. Regional dialects are further of two types: (i) those regional

dialects or variations which are spoken in the regions inside the valley of

Kashmir and (ii) those which are spoken in the regions outside the valley of

Kashmir. Kashmiri speaking area in the valley is ethno-semantically divided into three

regions: (1) Maraz (southern and south-eastern region), (2) Kamraz (northern and

north-western region) and (3) Srinagar and its neighboring areas. There are some

minor linguistic variations mainly at the phonological and lexical levels.

Kashmiri spoken in the three regions is not only mutually intelligible but quite

homogeneous. These dialectical variations can be t.mp3ed as different styles of

the same speech. Since Kashmiri, spoken in and around Srinagar has gained some social

prestige, very frequent ‘style switching’ takes places from Marazi or

Kamrazi styles to that of the style of speech spoken in Srinagar and its

neighboring areas. This phenomena of style switching is very common among the

educated speakers of Kashmiri. Kashmiri spoken in Srinagar and surrounding areas

continues to hold the prestige of being the standard variety which is used in

mass media and literature.

There are two main regional dialects, namely Poguli and Kashtawari spoken

outside the valley of Kashmiri (Koul and Schmidt 1984). Poguli is spoken in the

Pogul and Paristan valleys bordered on the east by Rambani and Siraji, and on

the west by mixed dialects of Lahanda and Pahari. The speakers of Poguli are

found mainly to the south, south-east and south-west of Banihal. Poguli shares

many linguistic features including 70%

vocabulary with Kashmiri (Koul and Schmidt 1984). Literate Poguli speakers of Pogul and Pakistan valleys speak standard

Kashmiri as well. Kashtawari is spoken in the Kashtawar valley, lying to the

south east of Kashmir. It is bordered on the south by Bhadarwahi, on the west by

Chibbali and Punchi, and on the east by Tibetan speaking region of Zanskar.

Kashtawari shares most of the linguistic features of standard Kashmiri, but

retains some archaic features which have disappeared from the latter. It shares

about 80% vocabulary with Kashmiri (Koul and Schmidt 1984).

No detailed sociolinguistic research work has been conducted to study

different speech variations of Kashmiri spoken by different communities and

speakers who belong to different areas, professions and occupations. In some

earlier works beginning with Grierson (1919: 234) distinction has been pointed

out in two speech variations of Hindus and Muslims, two major communities who

speak Kashmiri natively. Kachru (1969) has used the terms Sanskritized Kashmiri

and Persianized Kashmiri to denote the two style differences on the grounds of

some variations in pronunciation, morphology and vocabulary common among Hindus

and Muslims. It is true that most of the distinct vocabulary used by Hindus is

derived from Sanskrit and that used by

Muslims is derived from Person-Arabic sources. On considering the phonological and morphological variations (besides

vocabulary) between these two dialects, the terms used by Kachru do not appear

to be appropriate or adequate enough to represent the two socio-dialectical

variations of styles of speech. The dichotomy of these social dialects is not

always clear-cut. One can notice a process of style switching between the speakers

of these two dialects in terms of different situations and participants. The

frequency of this ‘style switching’ process between the speakers of these

two communities mainly depends on different situations and periods of contact

between the participants of the two communities at various social, educational

and professional levels. Koul (1986) and Dhar (1984) have presented co-relation

between certain linguistic and social

variations of Kashmiri at different social

and regional levels. The socio-linguistic variations of the language deserve a

detailed study.

Unique Characteristics

Kashmiri is closely related to Shina and some other languages of the

North-West frontier. It also shares some morphological features

such as pronominal suffixes with Sindhi and Lahanda. However, Kashmiri is different from all other Indo-Aryan languages

in certain phonological, morphological and syntactic features.

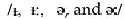

For example, Kashmiri has a set of central vowels , and dental affricates /ts/ and /tsh/ which are not found

in other Indo-Aryan languages. In a similar way, in Kashmiri

the finite verb always occurs in the second position with

the exception in relative clause constructions. The word order

in Kashmiri, thus, resembles the one in G.mp3an, Dutch, Icelandic,

Yiddish and a few other languages. These languages

f.mp3 a distinct set and are currently known as Verb Second

(V-2) languages. Note that the word order generated by V-2

languages is quite different from Verb middle languages such

as English. In a V-2 language, any constituent of a sentence

can precede the verb. It is worth mentioning here that

Kashmiri shows several unique features which are different from the above

mentioned other V-2 languages. , and dental affricates /ts/ and /tsh/ which are not found

in other Indo-Aryan languages. In a similar way, in Kashmiri

the finite verb always occurs in the second position with

the exception in relative clause constructions. The word order

in Kashmiri, thus, resembles the one in G.mp3an, Dutch, Icelandic,

Yiddish and a few other languages. These languages

f.mp3 a distinct set and are currently known as Verb Second

(V-2) languages. Note that the word order generated by V-2

languages is quite different from Verb middle languages such

as English. In a V-2 language, any constituent of a sentence

can precede the verb. It is worth mentioning here that

Kashmiri shows several unique features which are different from the above

mentioned other V-2 languages.

Script

Various scripts have been used for Kashmiri. The main scripts are: Sharda,

Devanagari, Roman and Perso-Arabic. The Sharda script, developed around the 10th

century, is the oldest script used for Kashmiri. The script was not developed

for writing Kashmiri. It was primarily used for writing Sanskrit by the local

scholars at that time. Besides a large number of Sanskrit literary works, old

Kashmiri works were written in this script. This script does not represent all

the phonetic characteristics of the Kashmiri language. It is now being used for

very restricted purposes (for writing horoscopes) by the priestly class of the

Kashmiri Pandit community. The Devanagari script with additional diacritical

marks is used for Kashmiri by writers and researchers in representing the data

from Kashmiri texts in their writings in Hindi related to language, literature

and culture. It is also used as an additional script (besides Perso-Arabic) or

alternate script in certain literary works, religious texts including devotional

songs written by Hindu writers outside the valley of Kashmir after their

migration from the valley. It is being used by a few journals namely Koshur

Samachar, Kshir

Bhawani Times, Vitasta, and Milchar

on regular basis. Certain amount of

inconsistency prevails in the use of diacritic signs. The diacritic signs for

writing Kashmiri in this script have recently been standardized and the computer

software is available for it. It is not yet used in all the publications. The

Roman script is also used for Kashmiri but is not very popular. The Roman script

with phonetic diacritic signs is used in the presentation of data from Kashmiri

in the linguistic and literary works related to the Kashmiri language and

literature written in English. It is also used in instructional materials for

teaching and or learning Kashmiri as a second/foreign language through the

medium of English. However, there is no unif.mp3ity in the use of diacritic

signs.

The Perso-Arabic script with additional diacritical marks now known as

Kashmiri script has been recognized as the official script for Kashmiri by the

Jammu and Kashmir Government and is now widely used in publications in the

language. It still lacks standardization (Koul 1996). The computer software is

available for writing Kashmiri in this script.

Learning of Kashmiri as a second/foreign language

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in learning Kashmiri

as a second/foreign language. Kashmiri is being taught as a second language at

the Northern Regional Language Centre (CIIL) Patiala since 1971. A limited

number of pedagogical materials in the from of language courses and

supplementary materials have been produced in Kashmiri so far. Kachru

(1969,1973) has made first serious attempt in this regard. Koul (1985,1995) has

prepared two textbooks for teaching basic and int.mp3ediate level courses in

Kashmiri at the NRLC Patiala. They introduce all major structures of the

Kashmiri language. Bhat (1982) and Raina(1995) have prepared readers in for

teaching Kashmiri at the first two levels at the sochool level. They contain

lessons on the Kashmiri script and some structures. Bhat (2001) has prepared an

audio-cassette course in Kashmiri with a manual useful for the second language

learners of Kashmiri.

The present book is essentially a self-instructional course. It contains 20

lessons presenting basic structures of the Kashmiri language. Each lesson

contains usually one major structure along with related patterns. All the

lessons consist of text, mostly in the f.mp3 of dialogues, followed by drills,

exercises, vocabulary and notes on grammar. Texts are given with equivalent

English translations. It is to be noted that these English translations have no

one to one correspondence with Kashmiri, either structurally or stylistically

but are intended, only to convey the general meaning.

Drills are provided for the oral practice of the structure and teachable

items introduced in each lesson. The types of drills introduced are:

Substitution drill, Repetition drill, Transformation drill, and Response drill.

The main types of exercises used in this book are: Fill in the blanks using

suitable words, completion of sentences, answering of questions, using of words

and phrases in sentences etc. The drills and exercise are designed to help the

development of learners’ linguistic competence in the language systematically.

The vocabulary section lists lexical items, which occur in the lesson for the

first time. The English meanings given for the lexical items are generally

restricted to the context they occur in the lesson. The notes on grammar are

provided from the functional point of view and the use of technical terms is

kept to the minimum. The learners may consult other sources (Kachru 1969, 1973,

Koul 1977, 1985, Koul and Hook 1984, Bhat 1986, and Wali and Koul 1997) for more

detailed grammatical descriptions. The appendix provides a list of classified

vocabulary in Kashmiri. The learners who use this book as a self-instructional

course must ensure that they practice drills and attempt exercises given in each

lesson with the assistance of a native speaker of Kashmiri or from the lessons

recorded, to be obtained from the publishers.

This book was first published in 1987. It is reprinted with minor revisions.

I would like to thank Mr. Sunil Fotedar for making

it available on net and encouraging me to bring out its second

reprint.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|