Language and Politics in Jammu and Kashmir:

Issues and Perspectives

- by K. Warikoo

Language is the most powerful means of

communication, vehicle of expression of cultural values and aspirations and

instrument of conserving culture. As such language is an important means to

acquire and preserve identity of a particular group or community. Language and

culture are interrelated because the language regions possess certain

homogeneity of culture and are characterized by common traits in history,

folklore and literature. Among various cultural symbol-religion, race, language,

traditions and customs, etc. that differentiate an ethnic group from the other,

language is the most potent cultural marker providing for group identity. Its

spatial spread over a fixed territory makes language more important than

religion as a basis of ethnic identity formation.

In the emerging world order, when rise of ethno-

nationalism is posing a major challenge to the nation state, political assertion

of language or religious identities has assumed importance. However, events in

Pakistan which was established in 1947 as an Islamic state on the basis of

religious factor, have demonstrated the inherent conflict between language and

religious identities. It was the language variable that led to the break-up of

Pakistan in 1971 and the creation of a new independent nation- Bangladesh.

Bengali language proved to be more powerful an ethnic factor than common Muslim

identity. Similarly political manifestation of language rivalry has now gained

primacy in the ongoing ethnic conflicts between Sindhis, Punjabis, Saraikis,

Baluchis and Urdu speakers in Pakistan, even though all of them belong to the

Muslim umma. Ironically, it is religion rather than language that has been the

key motivating and mobilizing factor in the present secessionist movement in

Kashmir. Yet there have been frequent though vague references by the political

and intellectual elite to propose various solutions to the problems on the basis

of 'Kashmiriat'. Since language and particularly mother tongue forms the core of

this much publicized concept of 'Kashmiriat', this study has been undertaken to

analyse the complex dynamics of language and politics in the multi-lingual state

of Jammu and Kashmir. Often described as a three-storeyed edifice composed of

three geographical divisions of Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh and Baltistan, bound

together by bonds of history and geography and linked together by a common

destiny, Jammu and Kashmir State presents a classic case of linguistic and

ethno- religious diversity.

Language Demography

An in-depth and objective study of the language

situation in Jammu and Kashmir State calls for an understanding of the language

demography of the State which would indicate the spatial distribution of various

linguistic groups and communities. This in turn reflects the variegated ethino

no- cultural mosaic of the State. The language and cultural areas are not only

correlated but are generally specific to a particular area (See Map at the end

of this chapter). For purposes of this study, J&K Census Reports of 1941,

1961, 1971 and 1981 have been relied upon. (No census has been carried out in

the State in 1951 and 1991). The population of various linguistic groups as

detailed in each of these Censuses, is given below in Tables 1 to 4.

Table 1

J&K: Major Linguistic Population Groups, 1941

Total Population of J&K (1941 Census)= 40,21,616

| Language |

J&K state |

Kashmir Province |

Jammu Province |

Ladakh* |

Gilgit, Gilgit Agency, Astor etc |

| Kashmiri |

15,49,460[1] |

13,69,537 |

1,78,390 |

1174 |

323 |

| Punjabi (Dogri) |

10,75,273[2] |

73,473[3] |

10,00,018 |

453 |

1329 |

| Rajasthani (Gujari)[4] |

2,83,741 |

92,392 |

1,87,980 |

Nil |

3369 |

| Western Paharis [5] |

5,31,319 |

1,70,432[6] |

3,60,870[7] |

5 |

12 |

| Hindustani[8] (Hindi & Urdu) |

1,78,528 |

10,631 |

1,67,368 |

22 |

507 |

| Lahnda (Pothwari) |

82,993 |

8 |

82,975[9] |

5 |

5 |

| Balti |

1,34,012 |

352 |

184 |

1,33,163 |

313 |

| Ladakhi |

46,953 |

230 |

299 |

46,420 |

4 |

| Shina (Dardi) |

84,604 |

7,888[10] |

114 |

13,562 |

63,040[11] |

| Burushaski[12] |

33,132 |

3 |

Nil |

244 |

32,885 |

| Tibetan |

503 |

26 |

145 |

317 |

15 |

* Before independence, Skardo/Baltistan (now in Palk-occupied

Kashmir/ Northern Areas) was a Tehsil of Ladakh District.

1. In the 1941 census, persons speaking Kishtwari

(11,170), Siraji (17,617), Rambani (1,202), Poguli (5,812) and Banjwahi (747),

totalling 36,548 persons have been included under the head Kashmiri.

2. Dogri has been taken as a dialect under Punjabi,

thereby enumerating 4,13,754 Punjabi speaking persons mainly in Mirpur

together with 6,59,995 Dogri speakers.

3. Out of this figure, 48,163 persons are form

Muzaffarabad (now in POK).

4. Gujari, the language of Gujars has been included with

Rajasthani.

5. Pahari, which is enumerated separately, is closely

connected with Gujari and is spoken in much the same areas.

6. Includes 1,55,595 persons in Muzaffarabad (now in POK).

7. Includes 2,36,713 persons in Poonch, Haveli, Mendhar.

8. Hindi and Urdu have been combined and enumerated as

Hindustani.

9. Nearly all (82,887 persons) are concentrated in

Mirpur.

10. Includes 7,785 persons in Baramulla (Gurez area).

11. Shina language is spoken chiefly in Gilgit area.

12. It is mainly spoken in Hunza, Nagar and Yasin.

Table 2

J&K: Major Linguistic Population Groups, 1961

Total Population of J&K, (1961 Census) = 35,60,976

| Language |

J&K State |

Kashmir Province |

Jammu Province |

Ladakh District |

| Kashmiri |

18 96,149 |

17,17,259 |

1,78,281 (Mainly in Doda) |

609 |

| Dogri |

8,69,199 |

1,784 |

8,67,201 |

214 |

| Gojri |

2,09,327 |

64,493 |

1,44,834 |

Nil |

| Ladakhi |

49,450 |

79 |

42 |

49,829 |

| Punjabi |

1,09,174 |

32,866 |

76,308 |

Nil |

| Balti |

33,458 |

514 |

38 |

32,905 (Miainly in Kargil) |

| Hindi |

22,323 |

2,494 |

19,868 |

61 |

| Urdu |

12,445 |

3,504 |

8,941 |

Nil |

| Dardi/Shina |

7,854 |

7,605 (Mainly in Gurez area of

Baramulla) |

30 |

219 |

| Tibetan |

2,076 |

Nil |

148 |

1,899 |

Table 3

J&K: Major Linguistic Population Groups, 1971

Total population of J&K, (1971 Census) = 46,16,632

| Language |

J&K State |

Kashmir Division |

Jammu Division |

Ladakh Division |

| Kashmiri |

24,53,430 |

21,75,588 |

2,75,070 |

772 |

| Dogri |

11,39,259 |

8,161 |

11,30,845 |

253 |

| Hindi* (Gujari) |

6,95,375 |

1,80,837 |

5,14,177 |

361 |

| Ladakhi |

59,823 |

1,446 |

1,562 |

56,815 |

| Punjabi |

1,59,098 |

46,316 |

1,12,258 |

524 |

| Lahanda (Pothwari) |

22,003 |

109 |

21,894 (Mainly in Rajauri) |

Nil |

| Urdu |

12,740 |

4,521 |

8,209 |

10 |

| Balti |

40,135 |

822 |

280 |

39,033 (Mainly in Kargil) |

| Shina |

10,274 |

9,276 (Mainly in Gurez area of

Bramulla) |

251 |

747 |

| Tibetan |

3,803 |

867 |

Nil |

2,936 |

* Gujari, the language of Gujars has been included with

Hindi.

Table 4

J&K: Major Linguistic Population Groups, 1981

Total population of J&K, (1981 Census) = 59,87,389

| Language |

J&K State |

Kashmir Division |

Jammu Division |

Ladakh Division |

| Kashmiri |

31,33,146 |

28,06,441 (Mainly in Doda Dist.) |

3,28,229 |

1,476 |

| Dogri |

14,54,441 |

2,943 |

14,51,329 |

169 |

| Hindi* (Gujari) |

10,12,808 |

2,55,310 (Mainly in Baramulla and

Kupwara Districts) |

7,67,344 (Mainly in Doda, Punch and

Rajauri Districts) |

155 |

| Ladakhi |

71,852 |

471 |

1,190 |

70,191 |

| Punjabi |

1,63,049 |

41,181 |

1,21,668 |

200 |

| Lahanda (Pothwari) |

13,184 |

21 |

13,163 |

Nil |

| Urdu |

6,867 |

3,830 |

3,019 |

18 |

| Balti |

47,701 |

811 |

Nil |

46,890 (Mainly in Kargil) |

| Shina (Dardi) |

15,017 |

12,159 (Mainly in Gurez area of

Baramula) |

Nil |

2,858 (Mainly in Dah Hanu) |

| Tibetan |

4,178 |

796 (Mainly in Srinagar) |

Nil |

3,382 (Mainly in Leh Tehsil) |

* Gujari, the language of Gujars has been included with

Hindi.

The people of J&K State, whether Kashmiris, Dogras,

Gujars-Bakarwals, Ladakhis, Baltis, Dards, etc. have in all the censuses

unambiguously identified their indigenous languages as their 'mother-tongues'

thereby consolidating their respective ethno-linguistic and cultural identities.

This is particularly important in view of the fact that the Muslims of the State

have thus acted in a manner quite different from that of Muslims in most of the

Indiar states.

It is also in stark contrast to the experience in

Punjab, where Hindus though speaking Punjabi at home earlier claimed Hindi as

their mother tongue during the census operations. Similarly, the Muslims in

various Indian States such as Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala etc. who

registered local languages as their mother-tongues in 1951 Census, opted for

Urdu in 1961 and afterwards, thereby leading to a dramatic rise in the number of

Urdu speaking persons in India. Same is the case with the Muslims of Uttar

Pradesh, who registered their language as Hindustani in 1951 Census, but have

been claiming Urdu as their mother tongue subsequently. This demonstrates the

urge of the Muslims in other Indian states to identify themselves with Urdu

rather than with Hindustani (the basic substratum of Hindi and Urdu, it does not

have any communal and politicised connotation) or the indigenous mother tongues,

in a bid to consolidate themselves as a distinct collective group linked

together by common bond of religion and Urdu which they believe to be

representing their Muslim cultural identity. Clearly these Muslims have moved

away from regional towards the religious identity.

It is precisely for avoiding any such communal

polarisation between Hindus and Muslims on the issue of Hindi and Urdu

languages, that the J&K State Census authorities decided in 1941 to club

Hindi and Urdu together and use Hindustani. This, however, resulted in inflating

the number of persons claiming Hindi and Urdu speakers to 1,78,528 (mostly in

Jammu province). R.G. Wreford, the then Census Commissioner admits it in his

report, saying that "The figures for Hindustani are inflated as the result

of the Urdu-Hindi controversy. Propapanda was carried on during the Census by

the adherents of both parties to the dispute with the result that many Hindus

gave Hindi as their mother tongue and many Muslims gave Urdu quite contrary to

the facts in the great majority of cases. The dispute is largely political and

so to keep politics out of the Census, it was decided to lump Hindi and Urdu

together as Hindustani".

In the 1961, 1971 and 1981 censuses, usage of the term

'Hindustani' has been discarded in favour of separate enumeration for Hindi and

Urdu speaking persons. The 1961 Census, which has treated Hindi and Gujari

language separately, (unlike the 1971 and 1981 censuses, where Gujari in

included into Hindi), should be taken as authentic base for calculating the

number of persons claiming Hindi as their mother tongue. Yet there is no denying

the fact that though respective mother tongues are spoken universally by various

ethnic groups in their households or among themselves, the people of the State

are generally bilingual or even trilingual in some cases. Thus if a Kashmiri

uses his mother tongue within his group, he uses Urdu, Hindi or Hindustani in

his conversation with the people from Jammu Province, Ladakh division and from

the rest of India. Similarly, a Dogra would use Dogri within his group, Punjabi

with his counterparts from Punjab and Delhi and Hindi or Hindustani with others.

Ladakhis would use Ladakhi among themselves and Hindi, Urdu or Hindustani with

others. English has also become popular, due to its common usage in

administrative offices, trade, industry, and educational institutions.

The prevalence of Urdu as a link language is not only

due to its being the official language, but also due to its popularisation

through the publication of books, newspapers and periodicals in large numbers.

Besides, the close socio- economic contacts between the people of the State and

rest of India, plus the impact of tourism, modernisation and educational

development have contributed to the use of Urdu and Hindi in the State, in

addition to the mother- tongues.

The Census Report of 1941 for Jammu and Kashmir,

provides an insight into the language situation in the State before

independence, i.e. before a large chunk of the State in Mirpur, Muzaffarabad and

Frontier Districts (Baltistan, Astore, Gilgit etc.) was occupied by Pakistan in

1947-48. This area is not known as Pak-occupied Kashmir/Northern Areas. The 1941

Census has listed Kashmiri, Dogri, Punjabi, Rajasthani, Western Pahari, Balti,

Ladakhi, Shina/Dardi and Burushaski as the main languages, spoken in the State.

The 1941 census has followed the general scheme of classification, whereby Dogri

and Gujari have been included as dialects under Punjabi and Rajasthani

respectively, which is likely to create confusion to the non-discerning reader.

However, the Census has provided a solution by indicating the actual number of

Dogri and Punjabi speakers as 6,59,945 and 4,13,754 respectively. Whereas the

Dogri speakers were concentrated in Jammu, Udhampur, Kathua and Chenani Jagir

districts, most of the Punjabi speakers were settled mainly in Mirpur and also

in Muzaffarabad (48,163 persons). Similarly out of 82,993 Lahnda speakers

(including those speaking Pothawri dialect), 82,887 persons were concentrated in

Mirpur district.

Gujari, the language of Gujars and Bakerwals (now

declared as Scheduled Tribes), was included as a dialect under Rajasthani due to

its close affinities with that language. But Pahari which is closely connected

with Gujari and continues to be spoken in much the same areas, was enumerated

separately. Thus we have 2,83,741 Gujari speakers and 5,31,319 Western Pahari

speakers (including those speaking Bhadrawahi, Gaddi, Padari, Sarori dialects).

Reasi, Jammu, Poonch, Kaveli, Mandhar, Baramulla, Anantnag and Muzaffarabad

districts were shown as the main concentration points of Gujari and W. Pahari

speakers, thereby testifying to their widespread distribution throughout the

State. The subsequent Census Reports of 1961, 1971 and 1981 have removed this

anomaly of enumerating Gujari and Pahari separately. However, the Census reports

of 1971 and 1981 have followed a new anomalous practice of including Gujari (Rajasthani),

Bhadrawahi, Padri with Hindi. This has not only inflated the numbers of those

claiming Hindi as their mother tongue but also camouflaged the actual strength

of Gujari speakers, thereby causing disenchantment among this tribal community.

As most of these Hindi albeit Gujari speakers have been

shown as concentrated in Baramulla, Kupwara, Punch, Rajouri and Doda districts,

their Gujar identity becomes obvious. The 1961 census, which does not mix up

Hindi with Gujari, puts the number of Gujari speakers at 2,09,327 and that of

Hindi speakers at 22,323. Urdu is placed next with only 12,445 persons claiming

it their mother tongue.

Tables 1 to 4 make it amply clear that Kashmiri

commands the largest number of speakers, with Dogri at second and Gujari at

third positions respectively. The number of Punjabi speakers in 1961, 1971 and

1981 Census Reports, actually reflects the number of Sikhs who have maintained

their language and culture, and who are concentrated mainly in Srinagar, Budgam,

Tral, Baramulla (all in Kashmir Province), Udhampur and Jammu. In case of Ladakh,

several ethno-linguistic identities emerge on the basis of mother tongue and

area of settlement. Ladakhis (people of Buddhist dominated ladakh district and

Zangskar) have claimed Ladakhi, popularly known as Bodhi as their mother tongue.

Interestingly Tibetan language has been consistently identified as distinct

language/mother tongue in all the Census Reports under review, and it is spoken

by the small group of Tibetan refugees settled in Srinagar and Leh. As against

this, the Shia Muslims of Kargil have claimed Balti, another dialect of Tibetan

language. The Baltis of Kargil are separated by the Line of Actual Control from

their ethno-linguistic brothers in Baltistan area of 'Northern Areas' in

Pak-occupied Kashmir who also speak the sam. Balti dialect. There are some

Dardic speaking pockets in Gurez area of Baramulla in Kashmir, Dras and Da Hanu

in Ladakh. The people of Hurza, Nagar and Yasin in the 'Northern Areas' of

Pak-occupied Kashmir, speak the Burushaski language. The State of Jammu and

Kashmir thus presents a classic case of linguistic and ethno-religious

diversity.

Neglect of Mother Tongues

It is established that Kashmiri ranks first among the

mother tongues of the State commanding the largest number of speakers, with

Dogri in second and Gujari in third position, followed by Punjabi, Bodhi, Balti,

Shina/Dardi in succession. Whereas Kashmiri has been included in the VIII

schedule of the Constitution of India, the demands of similar treatment for

Dogri and Bodhi are yet to be conceded. Conscious of the ethno-linguistic

heterogeneity of the State, the 'New Kashmir' Programme adopted by the Jammu and

Kashmir National Conference under the stewardship of Sheikh Abdulla as early as

1944, had envisaged the declaration of Kashmiri, Dogri, Balti, Dardi, Punjabi,

Hindi and Urdu as the national languages of the State Urdu was to be the 'lingua

franca' of the State. It was also laid down that:

"The state shall foster and encourage the growth

and development of these languages, by every possible means, including the

following:

(1) The establishment of State Language Academy, where

scholars and grammarians shall work to develop the languages,

(a) by perfecting and providing scripts,

(b) by enriching them through foreign translations,

(c) by studying their history,

(d) by producing dictionaries and text books.

(2) The founding of State scholarships for these

languages.

(3) The fostering of local press and publications in

local languages."

The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir has recognised Urdu

as the offficial language of the State, treating Kashmiri, Dogri, Balti, Dardi,

Punjabi Pahari and Ladakhi as regional languages. But the State Constitution has

not taken congnizance of the need "to protect the right of minorities to

conserve their distinctive language, script or culture; to provide adequate

facilities for instruction in the mother tongue, to the children of lmguistic

minorities", as has been explicitly provided in the Constitution of India

in Articles 29, 30 and 350.

What was laid down in the original manifesto of the

National Conference, has been fulfilled only to the extent of setting up of the

J&K Academy of Art, Culture and Languages. Circumstantial evidence indicates

that there has been an organised effort by the State political-bureaucratic

elite to stifle the growth of Kashmiri language and other local mother tongues.

It becomes obvious from the following facts:

(i) Teaching of Kashmiri has not been introduced at the

primary or secondary school levels in the State. Not only that, no textbooks

in Kashmiri are available even though a set of such books was prepared by

experts. The Post Graduate Department of Kashmiri has been created as a super

structure without any ground support at the primary and secondary levels. This

is despite the general desire among Kashmiri masses to have Kashmiri as a

medium of instruction particularly at the primary and middle levels of

education. This gets amply reflected in a survey, in which 83 per cent of the

respondents showed their preference for use of Kashmiri as a medium of

instruction at primary levels and 48 per cent preferred the same at middle

level of education, whereas 49 per cent wanted to have English at high or

higher secondary levels.

(ii) Notwithstanding the publication of hundreds of

newspapers and periodicals mostly in Urdu and some in English, hardly any

newspaper or periodical is published in any local language in the State. The

journal Sheeraza, which is brought out by the J&K Cultural Academy in

Kashmiri, Dogri, Gujari and Bodhi languages, has a limited circulation among

the literary circles. Local masses have to rely exclusively on Urdu and

English newspapers/periodicals published locally or coming from Punjab or

Delhi, though the people of the Valley would like to have Kashmiri newspapers.

A socio-linguistic survey in Kashmir revealed that 47 per cent of the

respondents reported their preference for local newspapers in Kashmiri

language. J&K State is perhaps the only Indian state where local language

press and publications are virtually absent.

(iii) Usage of Urdu has received official

patronage, it being the medium of instruction in primary and secondary levels.

Persi-Arabic script has been adopted for Kashmiri language. The functional

role of Kashmiri in the domain of written communication has been reduced to

minimum, as all personal letters, official correspondence etc. are written in

Urdu, English or Hindi languages. The Sharda script, though indigerous to

Kashmir, has been totally ignored. Not only that, the treasure of ancient MSS

in the Sharda script is decaying in various libraries/archives in J&K

State and needs immediate retrieval. Sharda script was used for preparing

horoscopes, though its usage is now restricted to a few practicing Brahmins.

With the result, this ancient tradition has gone into oblivion. Similarly, the

demands of ethno-religious minority of Kashmiri Hindus, presently living in

forced exile, for adopting Devnagri as an alternate script for Kashmiri

language have been ignored. With the result this sizeable minority of Kashmir,

has not only been deprived of access to the rich fund of Kashmiri language and

literature, but their right to preserve and promote their ancient cultural

heritage has also been denied. This is in clear contravention of the Article

29, 30 and 350 of Indian Constitution. On the other hand, the State government

has adopted Persi- Arabic script as an alternate script for Dogri and Punjabi

in addition to thereby displaying their motivated double standards. That

Devngari script has been in prevalence for Kashmiri is obvious from the

publication of several Kashmiri books/journals in this script. Not only that,

Maharaja Hari Singh of Jammu and Kashmir while conceding the demands of both

the Hindu and Muslim Communities, issued orders in late 1940 allowing the

usage of both Persian and Davnagri scripts in schools, even while the common

medium of instruction would be simple Urdu. Students were given the option of

choosing either of the two scripts for reading and writing.

(iv) During the past two decades or so, there have

been organised efforts by the Islamic fundamentalist sccial, cultural and

political organisations, often receiving assistance from foreign Muslim

countries, to saturate the Kashmiri language and culture with aggressive

revivalistic overtones. It is not a mere coincidence that all the names of

various militant organisations in Kashmir, titles of office-bearers, their

slogans and literature are in the highly Persianised-Arabicised form.

Similarly, names of hundreds of villages and towns in Kashmir were changed

from ancient indigenous Sanskritic form to Persian/Islamic names, by the State

government. To quote a Kashmiri writer, "Language was subverted through

substitution of Pan-Islamic morphology and taxonomy for the Kashmiri one.

Perfectly Islamic person names like Ghulam Mohammed, Ghulam Hassan, Abdul Aziz,

Ghulam Rasool which were abundantly common in Kashmir were substituted by

double decker names which were indistinguishable from Pakistani and Afghan

names". In this manner linguistic and cultural subversion was carried out

to "subsume the Kashmiri identity of Kashmir by a Pan-Islamic

identity" after "tampering with the racial and historical memory of

an ethnic sub-nationality through a Pan-Islamic ideal". Kashmir was thus

projected as "an un-annexed Islamic enclave" which should secede

from the secular and democratic India.

(v) Films Division of the Government of India,

which used to dub films in 13 Indian languages including Kashmiri for

exhibition among the local masses, stopped doing so at the instance of the

State administration. They were instead asked to do it in simple Urdu.

(vi) That the State bureaucracy even foiled the

attempts by Progress Publishers, Moscow, to start translation and publication

of Russian classics in Kashmir, is established by the following information

provided to this author by Raisa Tugasheva who was actively associated with

this programme.

"It was in 1972 that the Progress

Publishers, Moscow (successor to Foreign Language Publishing House which

published in 13 languages) decided to start publication of Kashmiri

translations of Russian literature. Some Urdu knowing scholars were recruited

for the task. Ms. Raisa rugasheva (who had worked as Urdu announcer at

Tashkent Radio for twenty years) was made Head and Editor-in-Chief of the

Kashmiri Section of Progress Publishers. Besides two Assistant editors and one

Kashmiri Muslim student at Moscow were associated with the Project. At the

first instance, a few books of Russian literature were taken up and later

translated into Kashmiri. One assistant editor Lena was sent to Kashmir for

further study. When a delegation of Progress Publishers visited Kashmir to

survey the potential and prospects of circulation of these books, their

proposal met with a hostile State government response. It was found that the

State administrative machinery was against publication and circulation of

Kashmiri translations of Russian books. With the result the whole project was

quietly wound up".

(vii) Central government grants provided to the

State Education Department from time to time for development of Kashmiri

language and literature have either been spent on other heads or allowed to

lapse. Similarly the 100 per cent financial assistance provided by the centre

for translation of Constitution of India into Kashmiri was not availed of.

Instead these funds were diverted to promotion of Urdu which was misleadingly

projected as the regional language of the State.

(viii) Dogri which is spoken in Jammu region

and the adjoining areas of Himachal Pradesh and Punjab, has been recognised as

one of the regional languages in the VI Schedule of the State's Constitution.

Though the Sahitya Academy started giving its awards for Dogri in 1970, the

people of Jammu have been demanding inclusion of Dogri in the VIII Schedule of

Constitution of India. When in mid-1992 the Central government was taking

steps to include Nepali, Konkani and Manipuri in the VIII Schedule, the Dogri

Sangharsh Morcha started a movement in Jammu pressing for acceptance of their

demand. Though the matter was raised in Parliament, nothing happened. The

Jammu people point to the rich literary heritage of Dogri, its wide prevalence

in J&K, Himachal Pradesh and Punjab and also the usage of easy Devnagri

script for this language, and their contribution to maintain national

integrity, as sufficient grounds for inclusion of Dogri in the VIII Schedule.

They are peeved at the discriminatory attitude of the Central government in

not accepting their demand which they allege to be under the political

interference of the Kashmiri politicians.

(ix) In Ladakh too Urdu was imposed as a medium

of instruction, though the majority of people there speak and write Ladakhi (Bodhi),

a dialect of Tibetan and which has a script of its own. It was during the

latter years of Dogra rule that Urdu was introduced as the official language

throughout the State including Ladakh. Even at that time the Ladakhi Buddhists

had resented the 'infliction of Urdu' as a medium of instruction in primary

schools. The report of the Kashmir-Raj Bodhi Maha Sabha, Srinagar (1935)

provides an insight into the sharp reaction evoked by this practice among the

local people. It states:

"The infliction of Urdu-to them a

completely foreign tongue-on the Ladakh Buddhists as a medium of instruction

in the primary stage is a pedagogical atrocity which accounts, in large

measure for their aversion to going to school. Nowhere in the world are boys

in the primary stage taught through the medium of a foreign tongue. And so,

the Buddhist boy whose mother tongue is Tibetan must struggle with the

complicacies of the Urdu script and acquire a knowledge of this alien tongue

in order to learn the rudiments of Arithmetic, Geography, and what not....

This deplorable and irrational practice is being upheld in face of the fact

that printed text books for all Primary school subjects do exist in Tibetan

and have been utilized with good results by the Moravian Mission at Leh".

Ironically even after the end of Dogra Raj, Urdu continues to be the medium of

instruction. Though Ladakhi and Arabic have also been introduced in government

schools alongwith English, private Islamic schools teach Urdu and Arabic only.

This educational policy has led to building up of segmented religious

identities as against a secular one, thereby polarising the traditional and

tolerant Ladakhi society on communal lines.

(x) Instead of recognising Gujari, the mother

tongue of more than six lakh Gujars, the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir has

included Pahari, as one of the regional languages in its VI schedule. This

anomalous situation is a result of the impression that Gujari is part of

Pahari, though it is actually more akin to Rajasthani. And the Census or 1941

has included Gujari under Rajasthani. Whereas the subsequent Censuses of 1961,

1971 and 1981 have not mentioned Pahari at all. This is one of the

contributory factors that have led to the Gujari-Pahari controversy, which has

been explained in the following pages. Gujars of Jammu and Kashmir have been

demanding their identification and enumeration by the Census authorities on

the basis of their tribal rather than linguistic identity, so as to avoid

overlapping with the Paharis and the consequent underestimation of their

population.

(xi) Balti, a dialect of the Tibetan language,

used to be written in the Tibetan script before the advent of Islam in

Baltistan in the sixteenth century. Numerous rock inscriptions which still

exist in Baltistan (in Pak- occupied Kashmir), are a living testimony to this

fact. Following the conversion of Baltis to Islam, indigenous Tibetan script

for Balti language was discarded "as profane". Instead, Persian

script was introduced even though it did not "suit the language due to

certain phonological differences". But after Baltistan was occupied by

Pakistan in 1948, Urdu has prevailed in the area. With the result the

indigenous Balti language has been further weakened due to heavy influence of

Persian and Urdu. The same is true of Baltis living in the Indian State of

Jammu and Kashmir. Baltis in Pakistan are deeply disturbed over the loss of

their inherited culture, particularly during the past two decades due to

"onslaught of religious fanaticism". This change is ascribed to the

Islamic Revolution in Iran, following which Maulvis flush with money entered

the area and banned singing, dancing and all forms of traditional cultural

activities. Interestingly, the Shia Muslims in the Kargil area of Ladakh, who

too speak the Balti language and share same culture with Baltis of Baltistan,

have been subjected to similar change. They have been allowed to be swayed

under the pernicious influence of Mullahs and Mujtahids, most of whom receive

theological training and support from Iran.

These mujtahids, have stripped the festivals and

ceremonies in Kargil of their traditional music and fanfare. The traditional

musicians-Doms, who used to play drums and wind pipe instruments on all festive

occasions, have been rendered jobless. This situation has resulted in the

destruction of rich folk, linguistic, literary and cultural heritage of Baltis.

The only saving grace is that most of the Balti folk literature is still

preserved in the oral unwritten tradition. Besides, there is an organised effort

inside Pak- occupied Baltistan, by Balti intellectuals led by Syed Abbas Kazmi

to revive the Balti heritage including its Tibetan script. The Baltistan

Research Centre, Skardo is doing a commendable job on this subject. Similar

efforts need to be initiated by J&K Cultural Academy inside Kargil area.

Foregoing discussion of the state of affairs of mother

tongues in Jammu and Kashmir State throws up important political issues. It

becomes clear that despite the local urge to preserve and promote their mother

tongues, whether it is Kashmiri, Dogri, Gujari, Bodhi or Balti, the same have

been denied their due place. This has been done as part of the calculated policy

of the Muslim bureaucracy and political leadership to subvert the indigenous

linguistic and ethno-cultural identities which inherit a composite cultural

heritage. Thus a supra national Muslim identity has been sought to be imposed in

different regions of the State, which essentially are different language and

culture areas. Simultaneously a whispering compaign was launched in Kashmir

alleging the central government's apathy towards Kashmiri language, which is,

however, belied by facts. Apart from inclusion of Kashmiri in the VIII Schedule,

Sahitya Academy has been giving awards for Kashmiri right from 1956 though it

started doing so for Dogri only in 1970. What is needed now is to remove the

existing imbalances and introduce Sahitya Academy awards for Gujari, Ladakhi (Bodhi)

and Balti, besides officially recognising Devnagari as alternate script for

Kashmiri.

Conclusion

The language geography of the State has changed after

1947 when a large chunk of the State was occupied by Pakistan, what is now known

as Pak-occupied Kashmir/ Northern Areas. The new ground situation is that all

the Kashmiri, Dogri, Gujari and Ladakhi speaking areas falls within the Northern

Areas. Yet some small pockets of Dardi speaking people-Buddhist Brukpas in Da

Hanu area of Ladakh, people of Dras (Ladakh) and Gurez (Baramulla) lie within

the Indian part of Jammu and Kashmir. Similarly, all the Pothawri (Lahanda)

speaking areas in Poonch, Mirpur etc. remain within the Pak-occupied Kashmir. As

regards the Baltis, they are divided between those living in Kargil in Indian

Ladakh and across the Line of Actual Control in Baltistan (Northern Areas). From

within the Kashmiri speaking community, the entire Kashmiri Hindu minority of

more than three lakhs has been forced out of the valley in 1980-90 by the

Islamist militants. Thus this significant and indigenous minority community has

been deprived of its ancient habitat and language culture area in the Kashmir

valley. Given the precarious condition of these displaced persons living in

forced exile in various parts of India and struggling for survival, their

language and culture are likely to be the worst casualty of their

ethnic-religious cleansing. The question of resettlement of this displaced

minority in their ancient birthland in a manner that ensures their ethnic-

linguistic and territorial homogeneity and adequate

constitutionaliadministrative safeguards for protection of their human rights,

is directly linked to the permanent solution of the Kashmir imbroglio.

A study of the language demography of Jammu and Kashmir

State establishes the fact that the Lahnda (Pothwari) speaking area falls almost

entirely across the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Pak-occupied Kashmir. That

the LAC on the western side coincides with the specific language culture area,

provides a natural permanence to the Line of Actual Control on ethno-linguistic

lines in this sector. This should provide a key to finding lasting solution to

vexed Kashmir problem between India and Pakistan. However, this is not true of

Balti speaking area, which remains divided by the Line of Actual Control between

Kargil area of Jammu and Kashmir in India and Baltistan region of Pak-occupied

Kashmir. That there is a renewed urge among the Baltis in Pak-occupied Kashmir

to revive their ancient Balti language and heritage only demonstrates their

cultural roots in Ladakh.

Regarding the evolution and affinities of various

mother tongues in Jammu and Kashmir, it is established that most of the

languages are rooted in or have close affinities with the Indo-Aryan languages.

Whereas Dogri is closely related to Punjabi, Gujari is akin to Rajasthani.

Grierson's theory of Kashmiri belonging to the Dardic branch of languages has

been disputed by the insider view emanating from Kashmir and e]sewhere. Most of

the linguistic researches conducted in Kashmir during the past forty years, have

established that Kashmiri bears close resemblance to Sanskritic languages,

thereby testifying to the close civilisational contacts and ties between Kashmir

and India since ancient times. Grierson who has misleadingly adopted the

religious distinction between 'Hindu Kashmiri' and 'Muslim Kashmiri' has

actually followed the colonial approach towards non-European sccieties.

Ironically Grierson's theory has been used as premier by an American geographer,

J.E. Schwartzberg has advocated the merger of Kashmir valley with the Dardic

speaking areas of Pak- occupied Kashmir on the basis of lmguistic and cultural

affinity. Grierson's theory has since been disputed. Besides, the fact remains

that the people of Kashmir valley are not only linguistically different from

those living across the Line of Control in Pak-occupied Kashmir, but also have

different cultural moorings and social ethos. Though Ladakhi and Balti belong to

the Tibeto-Burman group of languages, the presence of Sanskritic impact among

the Garkuns of Ladakh is a living example of the extent of Indian cultural

presence in this remote area. Given the importance of the subject, it is

incumbent upon the linguists and anthropologists in India to unravel the

mysteries of evolution and affinities of various mother tongues of Jammu and

Kashmir State, in the broader context of race movement and civilisational

evolution in north and north western India.

Kashmiri is the main language spoken in the State, its

spatial distribution being limited to the central valley of Kashmir and some

parts of Doda. Though Kashmiri has no 'functional role as a written language'

now, it is "overwhelmingly the language of personal and in-group

communication. It is the medium of dreams, mental arithmetic and reflection, of

communication within the family, with friends and in market places, in places of

worship etc.'' According to a survey, the Kashmiris view their language as

"an integral part of their identity" and want it to be accorded its

due role in the fields of education, mass-media and administration. The neglect

of mother tongues by the State is the most salient language issue in Jammu and

Kashrnir, and the earlier it is remedied, the better. However, the only silver

lining is ihat both Kashmiri Hindus and Muslims have identified Kashmiri as

their mother tongue.

Though Pahari has not been enumerated as a separate

language in the J&K State Census Reports of 1961, 1971 and 1981, of late

there have been demands for grant of some concessions to 'Paharis' in the State.

The Pahari versus Gujar issue is a potential source of ethnic conflict as both

the Pahari and Gujar interests are in conflict with each other. Both the Pahari

and Gujar identities overlap in certain aspects particularly their hill

settlement pattern and some common language features. The grant of Scheduled

Tribe status on 19th April 1991 by the central government, entitles the Gujars-the

third largest community in the State, to preferential treatment in government

services, educational, professional and technical education etc. Gujars also

claim propotionate representation in the State Assembly. The non- Gujar Muslims

of the State have been peeved at the conferment of Scheduled Tribe status and

its benefits to the Gujars. They have now demanded similar concession and the

privileges associated with it for the 'Paharis' of Rajouri, Poonch, Kupwara and

Baramulla districts, i.e., where the Gujars are in sizeable numbers. The central

government decision to meet the demand of Gujars has also evoked some reaction

from the local press. The new 'Pahari' demand has been backed by the valley

dominated political and bureaucratic Muslim elite, which has succeeded in

persuading the State Governor to take a few steps in this direction. On 17 May

1992, the non-Gujar 'Pahari Board' was set up, with eight Kashmiri Muslims,

eight Rajput Muslims, two Syeds and four non-Muslims as its members. On 18

December 1993, the State Governor, General K. V. Krishna Rao issued a statement

urging the central government to declare the Paharis as Scheduled Tribes.

Obviously, the J&K State administration is trying

to construct new identities such as 'Paharis', in a bid to undermine the Gujars

and their ethno-linguistic identity in the areas where they are dominant. That

is why the demands of 'Paharis' of Rajouri, Poonch, Kupwara and Baramulla,

(where Gujars are concentrated) are raised, whereas the backward and neglected

hill people of Ramban, Kishtwar, Padar and Bhadarwah, who speak distinct

dialects of Rambani, Kishtwari, Padari and Bhadarwahi, have been excluded from

the purview of the so called 'Pahari'. This is a subtle move to deprive the

Gujars of their numerical advantage and fully marginalise them in the political,

administrative and other institutional structures of the State.

The existing spatial distribution of Gujar speakers,

does provide some sort of linguistic territorial homogeneity, which however,

needs to be further consolidated to help in preservation and promotion of Gujari

language and ethno- cultural heritage and fulfilling their socio-economic and

political aspirations within the State. Inclusion of Gujari as one of the

regional languages in the VI schedule of state's Constitution and the Sahitya

Academy awards for Gujari writers, are basic steps that need to be taken

urgently.

That the Gujars are concentrated in specific border

belts surrounding the main Kashmiri speaking area, which mostly fali within the

Indian side of Line of Actual Control, is yet another aspect of political

importance. It is not only a physical obstacle in the way of attaining the goals

of the ongoing secessionist movement based on Pan-Islamic- Kashmiri identities,

it also demonstrates that barring some possible minor adjustments here and

there, the present LAC provides the best possible solution to the Kashmir

problem.

As already stated, all the Census reports have made a

clear distinction between the Ladakhi (Bhotia) and Tibetan speaking persons in

Ladakh, former being indigenous Ladakhis and the latter being Tibetan refugee

settlers. Interestingly, various political activist groups such as

"Himalayan Committee for Action on Tibet", "Himalayan Buddhist

Cultural Association", "Tibet Sangharsh Samiti" etc. which have

been spreaheading in India the campaign for Tibet's independence, and have

opened their branches in various Himalayan States of India, have been demanding

the inclusion of Bhotia language in the VIII Schedule of the Indian

Constitution. At the same time, there have been sustained efforts by the Tibetan

scholars at Dharamshala or abroad, towards preparing a unified system of Tibetan

language so that the same script, dialect etc. is applied to all the Bhotia/Tibetan

speaking peoples whether in Indian Himalayas or elsewhere. This raises the

question of Tibetanisation of society, culture and politics of the Indian

Himalayas partieularly in Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh,

Kalimpong, Darjeeling etc. It has been noticed that Tibetan refugees living in

these areas never use local dialect and seek to exercise their cultural hegemony

over the local Buddhist inhabitants. Due to divergent modes of economic activity

being followed by the Tibetan refugees and the indigenous Buddhists in this

Himalayan region, the former being engaged in marketing and industrial

activities and the latter being involved in primary agrarian economy, there have

been social conflicts between these two culturally similar groups with the

locals viewing the Tibetan refugees as exploiters. Such a conflict has been

experienced in Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh etc. It becomes

imperative for the concerned government and non-government agencies to ensure

that the indigenous Bhotia/Ladakhi and even Balti ethno-linguistic heritage is

preserved and promoted.

State government's policy towards local mother tongues

including Kashmiri, reflects the political dynamics of Muslim majoritarianism,

in which supra-national religious ethnicity has been artifically superimposed

over the linguistic ethnicity. This has been done with the object of bringing

Kashmiri Muslims closer to the Muslim Ummah in the subcontinent, and

particularly with the adjoining Islamic State of Pakistan. This task has been

carried forward by numerous Islamic political, social and cultural institutions

particularly the Jamat-i-Islami, Ahl-e-Hadis, Anjuman Tableegh-i-Islam etc. and

the madrassahs or even public schools run by these organistions, all of which

have been preaching and promoting Islamic world view both in political, social

and cultural affairs. With the result a firm ideological base has been prepared

to mould the political and cultural views of Kashmiri Muslims on religious lines

rather than ethno- linguistic/cultural basis, thereby negating the idnigenous

secular and composite cultural heritage. The same thing has happened in

Pak-occupied Kashmir (including Northern Areas), where Urdu-the national

language of Pakistan, has been imposed and popularised, and local mother

tongues- Pothwari, Khowar, Burushaski, Dardi/Shina and Balti remain neglected.

Whereas adoption of such a policy by the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is

understandable, it is quite ironical and unthinkable as to how such a state of

affairs has been al]owed in Jammu and Kashmir State, part of the secular and

democratic Republic of India which has otherwise provided specific

constitutional safeguards for promotion of mother-tongues and protection of

rights of linguistic and cultural minorities.

It is surprising that the neglect of Kashmiri has never

been a theme of unrest and anti-Indian movement in Kashmir. It is mainly because

the Kashmiri Muslims have been swayed by their intellectual elite and political

leaders of all hues (whether in power or out of it), most of whom have been

educated at the Aligarh Muslim University, thereby imbibing the spirit of

Aligarh movement which regards Urdu as the symbol of Muslim cultural identity.

This policy is derived from the Muslim League strategy adopted so successfully

by M.A. Jinnah, "for political mobilization of the Muslim Community around

the symbols of Muslim identification-Islam, Urdu and the new slogan of

Pakistan". that explains why primacy has been given to Islam instead of

language, thereby consolidating the religious divide between Kashmiri Muslims

and Hindus who otherwise inherit same language, habitat and way of life. True

spirit of Kashmiriat can be restored only after giving rightful place to the

indigenous Kashmiri language and culture. Besides steps need to be taken to

promote other mother tongues of the state-Dogri, Gujari, Bodhi (Ladakhi) and

Balti. Whereas the case of Dogri for inclusion in VIII Schedule of Constitution

of India needs to be considered favourably, Sahitya Academy should give awards

for literary works in Gujari and Bodhi as is done by it for Maithili and

Rajasthani which are not listed in the VIII Schedule. Devnagri should be

recognised as alternate script for Kashmiri language which will meet the long

standing demand of the sizeable ethno-religious minority of Kashmiri Hindus. The

Linguistic Survey of India and the Census Commissioner of India need to review

Grierson's classification and evolve a suitable enumeration code and proper

classification marks for various languages and mother tongues prevalent in Jammu

and Kashmir, so that the linguistic and cultural aspirations of numerous ethnic-

linguistic groups in the State are duly reflected and protected.

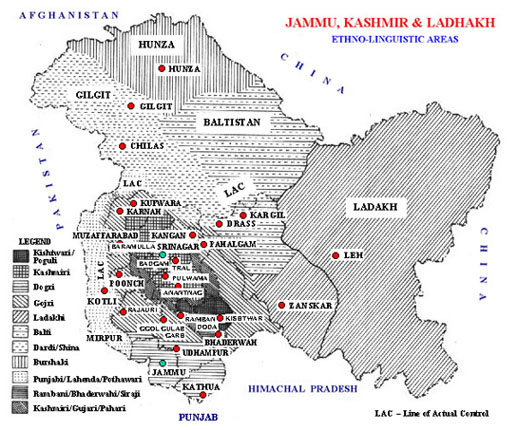

Jammu, Kashmir & Ladakh

Ethno-Linguistic Areas

Legend (Top to bottom as it is not readable

from the map):

Kishtwari/Poguli, Kashmiri, Dogri, Gojri, Ladakhi, Balti,

Dardi/Shina,

Burshaski, Punjabi/Lahenda/Pothawari, Rambani/Bhaderwahi/Siraji,

Kashmiri/Gujari/Pahari

About the Author:

K. Warikoo (born in Srinagar, 1951) is

Associate Professor of Central Asian Studies, School of International

Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. His major publications

include:

1. Central Asia and Kashmir: A Study in the Context

of Anglo-Russian Rivalry;

2. Ethnicity and Politics in Central Asia;

3. Afghanistan Factor in Central and South Asian

Politics;

4. Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh: A Comprehensive

Bibliography;

5. Central Asia: Emerging New Order, and

6. Society and Culture in the Himalayas. |

|