|

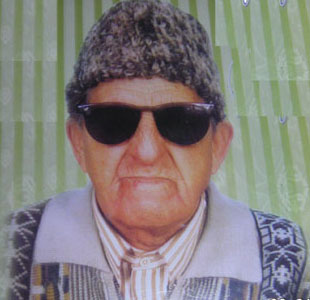

Ghulam Hassan Sofi- The undisputed Melody King of Kashmir.

Photo Courtesy: Rakesh Kaul

Melody,

meditation and melancholy:

A

tribute to Hasan Suif

by Haseeb A Drabu

Obituaries

are written for people who die, Ghulam Hasan Sofi never will. Haseeb A Drabu records some facets of the legend’s life and reveals the

nuances of his craft.

Most singers sing for a living. Very few live

to sing. Almost no singer lives his songs. Hasan Sofi did all three. What

distinguished him from all other singers is that he lived his songs. Looking

back and reminiscing, it would appear as if he sang only either to anticipate or

to rationalise his own life and that of many others. Every facet of his life, from his being a prodigy to the neglect towards the end of his

life, has been

described by the songs that he sang.

His famous song, taethi

cha diwan aane khali, kyoh kali kar tharav, is a mystical explanation of

the fact that his voice - an embodiment of melody, melancholy and mystery -

with no formal training was divinely ordained. He had been given his voice, as

if in lieu if the visual impairment that he was born with.

This should not come as a surprise considering

that his father had sought him from the darbar of Hazrat Moin-ud-din Chisti. The

greatest Sufi saint of the land seems to have blessed the unborn Hasan Sofi. After

his birth, going toAjmer

sharif, along with his father, became an annual pilgrimage. He owed his

spiritual allegiance to the chisiti silsila and in this his murshid was Zia

sahib of Pampore. It is during the visits to Ajmer

that he was exposed to music through qawaalis which seemed to have forged

a lasting association of sufism and singing in him.

The singer in him was awakened by his

surroundings. This

was a period in Kashmir

when Hafiz nagma was at its peak. One of the most famous hafizas of that time, was a woman called

Gill, who was sought after in Lahore

and Punjab. Such was her pre-eminence that in the shehre khaas, a popular adage was:

(mirwaiz)

rosulyun waaz, omar pranun maaz, amriun saaz, te gilli hund naaz (dancing

etiquette). Hafiza Gill used to reside at Dalgate in the neighborhood of Sofi.

He was so taken in by her singing that he would often eavesdrop near her gate.

One

day she caught him snooping and asked him why he was there, ”I love your

voice” replied young Sofi. Gill ded, as he would call her in later

years, took him under her wings and inquired of him whether he knows to how play

any musical instruments, perhaps thinking of including him in her troupe. Hasan

Sofi told her that he can’t play any instruments; she encouraged him to learn.

The

next we know is that the young boy pestered his father, Wahab Sofi, to buy him a

Sarangi. The father relented and a sarangi was bought from Tota of Nawa Bazar, a

famous Sarangi maker for the princely sum of Rs.2.50. Soon Sofi was adept at

playing it. In later years, such was his talent and dedication that he learned

to play all instruments used in Kashmiri music, known as the panch hathyar: Sareng,

Baje, rabab, knut, and tumbak naer.

His initiation into singing was done by Mohamed

Subhan. Every

evening Mohammad Subhan would conduct a mehfil, singing with him till

late hours. Eventually, Sofi got hold of singing in rhythm.

However, it was Ghulam Mohammad Tanki from the

neighbourhood who recognised the prodigious talent when he was just about 20.

Tanki introduced him to the legendary Amrit Lal Maini, Officer on Special Duty

in the Radio Kashmir. Maini gave him a break in Radio Kashmir, in early 1950's

and the rest as they say is history.

Except, in this case, the history is not well recorded. Officially, Hasan Sofi was born

on 8th July, 1932 at Dalgate. He came from the Hanji clan who make a

living off the Dal lake and are not particularly known for cultural pursuits. He

married a widow and adopted her daughter from the first marriage and continued

to live in the Dal. To come from a very

underprivileged background and achieve such heights demands respect.

Hasan Sofi started

his career singing Chakir and within no time mastered it. His first co-singer

was Habibullah Bomboo. Rahman Dar’s Sheesh Rang that he sung is still

considered to be the crowning glory of the genre of Chekr. Over time, he moved away from this form to evolve his own unique form of

modern Kashmiri ghazal singing, which was more modern and accessible to the

newer audience that was now listening in from the new beams of the radio rather

than as sit-in audience.

Remarkably, even as he did this and brought

about a paradigm shift in the art of singing, he stuck to being a purist in form

and rendition. Sofi’s passion for purity and the oral tradition enabled him to

compose most of his songs himself. Not many people know that he sang even the famous

song, Rinde poosh maal gindnai drai lolo

in the film Rasool Mir.

He

was fondly remembered by friends as ‘hazar daastan’ for being innovative and

versatile within the tradition. Perhaps

one of his best qualities that set him apart from some of his contemporaries and

which might, paradoxically and partly, explain his rather sad and neglected end

was his approach to music and poetry as a purist.

In one of his interviews for Prasar Bharati

Broadcasting corporation a few years ago, Sufi’s message to the younger

generation of Kashmiri singers reiterated the significance of purity of language,

tradition and diction. Money

or fame would not lure him towards anything that he would consider hybrid or

‘filmy’ or ‘paerum’.

He would say that if you wanted to sing in Kashmiri, you had to understand the verse in its totality and find the

appropriate notes in the local tradition to which the song belonged. This he

practised himself to a perfection.

At

the peak of his career, his songs reflected a perfect weave of poetry, emotion

and melody and a talent for capturing the essence and mood of lyrics in

different genres ranging from the serious mystical renderings of Rajab Hamid’s Afsoos Duniya…

to gazaals like tsche looguth sorme chachman, me korthum dil ubelyi, to lighter folk

songs like chon paknooy parzanovmayi dooryie, walay Kasturiyee.

From

romance to spirituality, he would sing with seamless ease and feeling. In doing

so, he would drown in his experience of the song and leave indelible imprints on

the souls of his audience. His ability to lift his listeners above earthly

concerns was supreme as was so evocatively done in many of his songs song

especially, afsoos duniya kansi na luob,

Zamanai pokene hamdam, Ye Na Chhun Duniya and many others.

His

greatest assets as a singer was that he was quite at home rendering the

mysticism of Shams Faqir, the romantism of Rasool Mir, the revolutionary zeal of

Mahjoor, the radicalism of Nadim, and the devotion of Wahab Khar. All this was

done only with just style and intonations; not supported by music. Can anyone

else even try this!

This

is a huge achievement considering the fact that the musical accompaniments in Kashmiri

music, principally the sarangi, and harmonium, weren’t evolved

enough. Frankly, there was no musical variation across his songs. To put it

bluntly, his singing

was not about music; but about melody. It was pure

melody of his voice laden as it was a palpable feeling for the lyrics.

What

took his songs from the ear to the heart was the mystical acuteness of feeling

for the song in his singing. It is nothing short of being divine. The

devotion that he brings into jaan wandyo

haan be paan wandiya is reflective of the Islam that we in Kashmir

have been practiced; no apologies, no compromises. The

philosophical discourse in tan nare daz

arrival kyoh kale kar tharaw was enhanced by his singing. Therein lay his

greatness.

He

didn’t merely sing songs, he vocalized the cultural philosophy of the Kashmir

Valley. Not only his style his sensibilities too were deeply Kashmiri.

As a singer and artist, it seems that Sofi

found his spirituality through his songs and will live forever as part of our

rich musical heritage and folk andromantic

lore- a heritage dating back and

underpinning a local, syncretic musical-mystical tradition that cuts across the

religious, gender, class and rural urban divides.

Incidentally, Sofi was not completely blind as

most people tend to believe. In his younger days, he used to go for movies and

many old timers remember seeing him bicycle regal cinema to Lal-chowk.

The death of Sofi as a person, even though he

claimed that he had received (materially) what was his share, is a poignant

reminder of the failure of Kashmiri society as a whole in supporting him and

fulfilling our obligations towards him in his years of decline. Perhaps, the final years of Sofi and his guarded pleas for help and how

he died is a sign of the decay and decadence of a cultural heritage.

For such a great and accomplished singer, his

ambitions were pretty modest. His only dream in life was to become a music

composer in the station! But there were certain officers in the station who

being jealous of his singing prowess and also his music composing capabilities

didn’t allow that to happen. He worked in the Radio Kashmir for 29 years at

very low levels.

It

is a great tragedy of our society and a shame that for the last few years of his

life, Sofi was living in oblivion. After his throat lost grip on tunes and his

heath deteriorated, he was deserted by his fans and even family. The culture

entrepreneurs, who have mushroomed in Kashmir

after 1994, also left him in lurch. A close but impoverished relative in

Rainawari pocket of downtown offered shelter to the legend during his hard and

testing years.

He

often complained and legitimately so, that nobody was coming forward to help him

despite his pleas. He accused several composers of plagiarising his songs and

tunes. I am sure he must have dawn solace from his own song, Dil

khot aath thaze kole, zahan kaa mainsih kahan aav, nile-wat lalnow laali.

It

is ironic that there is not a single decent collection of the legendary

singer’s songs available. Most of what he has sung is with the Radio Kashmir, Srinagar

but it has not been made accessible. Nor have the new technologies, like

digital, been used to give the recording a better edge.

As

an artist, he could be very temperamental. Even though

he was visually impaired, he could gauge the mood of audience – whether they

are attentive or not. And at times he would refuse to sing just because he would

feel that the gathering was not quite up there.

One

evening when he was performing at a private party, one of the guest asked him to

sing a foot tapping folk song, Dimyo

dilase gande valase, partho gilas kulnee tal he felt offended to be asked

to sing a light song sung by someone else and got up and went away!

What was it about Sofi that he enthralled three

generations of Kashmiris and is getting registered with the fourth one as well? What

made Ghulam Hasan Sofi such a great artist is that he didn’t just sing songs;

he vocalized Kashmiri culture. In doing so – and herein lies his greatest

contribution not only to the culture of J&K but to the cultural nationalism

of -- he opened the doors to the average Kashmir like me to explore the fascinating world of Samad

Mir, Wahab Khar, Waza Mahmud, Shamas Faqir, Mahmud Gami and Nyame sahib.

This

significance of this cannot be underestimated in a situation where the

language is a dying or an endangered one. Speaking for myself, there was no way

that I could have got into the philosophy of Shams Faqir or Samad Mir had it not

been for Ghulam Hasan Sofi. Rasa Javedani would have not been in the realm of my

consciousness, nor would have the terms zeer bum or rattan deep been

a part of my lexicon. Not only his was his style Kashmiri but his

sensibilities were truly Kashmiri. In that sense he was a ethno-musicologist.

While

it is well accepted that Sofi contributed to the music of the Valley, what has

not been appreciated is his role in the cultural revival of Kashmir

. If there were to be one living symbol of my ethno-cultural sensibility as a Kashmiri,

the most tractable one, it would be have to be him.

One

of his personal favourites that gives you an insight into what his own innermost

beliefs and philosophy was, kam kam sikender ayi matyo kati chhu haetim tai

dourah karith tim drayi matyo jaai katyu chhai. His eyes would get moistened

while singing it, showing how he had imbibed the transitory nature of this life

and its glory.

All

that we, those who were blessed to listen to him and privileged to meet him (my

regret is that despite meeting him so many times, I didn’t photograph myself with

him), can pray for is that Allah grant him what he

sang so soulfully, chui saawale nabi, tatte moklavaizaem, Yeti aase allam geer tai lo. May

Allah grant him the same peace and solace that he gave to millions of Kashmiris

by his soulful singing.

(Originally published in Greater Kashmir, reproduced here with

permission of

the author)

|

|

Title

|

wma

|

rm

|

mp3

|

|

Afsoos Duniya kansiya' na lob samsaar sity'e

|

|

|

|

|

Cho'n pakinuyee parzanomae

dooriye

|

|

|

|

|

Tanai roodum n hyes tai hosh

|

|

|

|

|

Chana'e bar tal ravam racha'e aawaaz vach'e

no

|

|

|

|

|

Che logath soram chachm'n , may koratham dil

|

|

|

|

|

Katiya myan'e maashok mat dit zor

|

|

|

|

|

Chukh so'n jigar gosh, jaan-e-n mas'e rosh

|

|

|

|

|

Jaan vandiyon haab-paan

vandiyon

|

|

|

|

|

Nyaree latee'e, bar ch vathiyey'e

|

|

|

|

|

Soz Ashkun Boz

|

|

|

|

|

Aem yaar Kornas

|

|

|

|

|

Bal Pyaras

Ashmuqam

|

|

|

|

|

Aftab deeshith

|

|

|

|

|

More chyon chhu

sombul, howut yaar kaman

|

|

|

|

|

Yaar yikhna chhum kraar poshan

|

|

|

|

|

Paan aeshko, chhui katyu thhikana

|

|

|

|

|

Ner katiye chhum karaan

|

|

|

|

|

Walo maar mati yaar karo

|

|

|

|

|

Tche kemyoo karnai taeweez pan

|

|

|

|

|

Kyoho kali karoo thhahraaw

|

|

|

|

|

Zamanai pokene hamdam

|

|

|

|

|

Chaneros pyala goum

|

|

|

|

|

Chhum ashque naaran

|

|

|

|

|

Nundbani maashooq

|

|

|

|

|

Rozoo rozoo bozoo

|

|

|

|

|

Sitamgare chhanave isharave

|

|

|

|

|

Yee gome panas

|

|

|

|

|

Mo chhaye rozuh mahinave

|

|

|

|

|

Brahm Dith Saqi

|

|

|

|

|

Walo Jadgaroo

|

|

|

|

|

Nawas Vandsay Sar

|

|

|

|

|

Ye Na Chhun Duniya

|

|

|

|

|

Betabai Korthas Walo

|

|

|

|

|

Wale Kaaley Raway

|

|

|

|

|

Grees Kouri

|

|

|

|

|

walai aaz

vasiye (with

Raj Begum)

|

|

|

|

|