|

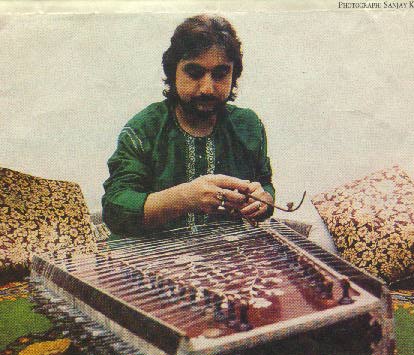

Pandit Bhajan Sopori - The coolest one

- Ashish Sharma

Pandit Bhajan Sopori

Photograph: Sanjay K. Sharma

For Pandit Bhajan Sopori and music lovers, the

santoor is

a delightful reminder of the Kashmir Valley

The melodious tinkle of the

santoor instantly transposes you to the world beyond. Not without reason. The

instrument is integral part of Kashmir as the Jhelum. And Pandit Bhajan Sopori

is one of its celebrated exponents, despite having made the scorched concrete of

Delhi his home. But his tenuous links with the Valley haven't diminished the

magic quality of his santoor's mellifluous strains. If the achievement needed

affirmation, then the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award, which came his way recently,

is certainly one. The journey to the honour has been anything but simple.

Adapting the instrument to classical music has led Sopori, for instance, to

experiment with more than a dozen different forms with slight variations. Says

he: "I've moulded the original instrument according to my need. The

original santoor, which used to be played with Sufi devotional music, is an

instrument of one-and-a-half octaves, but my santoor is a three-octave device

and has an effective range of around four-and-a-half octaves. There are 100

strings, as in the original, but these are spread over 25 bridges, four strings

to each bridge. This helps in creating depth in the instrument and as the

vibrations traverse the octaves, the process is actually perceptible as in the

sarod and the sitar."

Sopori adds: "The idea isn't just to

brighten the instrument's tone, but also to add to the depth of the sur,

for that is what counts in classical music. Which is why I have been able to

play 30-40 minutes of alaap in my recitals and such complicated ragas

as Marwa and Megh. So much so, that I've played duets with

artistes of the stature of V. C. Jog, the violinist. Recently, I presented dhamar

to the accompaniment of the pakhawaj. Shortly, I'll be playing the tappa."

It is not that the instrument itself is a new creation.

Far from it. But there are conflicting views on its origin. Says Sopori:

"There are those who believe it was brought to India via Central Asia. But

the belief of our gharana is that it's the same instrument that was

popular in the Shaivite devotional tradition in Kashmir and then passed on to

the Sufi music legacy that overtook the Valley after the Conversion." This

is confirmcd by the fact that even the wood used in the manufacture of the

santoor has been traditionally worshipped. Also it has never been a lok vadya

as suggested in some quarters. It has always been associated with classical

devotional music. The son and disciple of Pandit S.N. Sopori has eminently

carved out a niche for himself. Performing in public for the past 36 years -

since the age of 10, in fact - his dedication has ensured a considerable

visibility on the concert circuit with innumerable performances in India and

abroad, many records in the market, a number of awards and the inevitable

disciples. He combines all this with a job in All India Radio and the constant

demands that are made on him as a music director. He has composed music for

telefilms (Mahaan, Zameen and Yatra), a TV serial on adult

education (Chauraha) and a number of short films on Kashmir. He's also

the music director of a series on love stories, being readied for telecast on

Zee-TV shortly.

Clearly, he has his hands full at the moment. Which is

something music lovers wholly approve of.

|