|

A

Sociolinguistic Profile of Kashmiri

|

The

research on the linguistic aspects of the Kashmiri language is very inadequate

and fragmentary; therefore, a clear sociolinguistic profile of the language has

not emerged as yet. There are several reasons for this lack of research on

Kashmiri. Consider the following 1 observation (Kachru, 1969) [1],

The last two decades, especially

after 1955, have been of substantial linguistic activity on the Indian

sub-continent. A large number of Indic languages have been analyzed for the

first time, and new analyses of many languages have been worked out following

contemporary linguistic models. By and large, this linguistic interest has

left Kashmiri and other Dardic languages untouched. There are two main reasons

for this neglect of the Dardic languages. First, politically, the task is

difficult since the Dardic language area spreads over three political

boundaries and involves three countries (i.e. Afghanistan, sections of the

western part of Pakistan, and the northern part of India). Second,

geographically, the terrain is not easily accessible. Thus there continues to

be a great shortage of reliable and detailed linguistic literature on the

Dardic language family.

In the following pages, some basic

information is presented which should be of interest as a background for the

study of Kashmiri, to someone who is studying the language.

At present, the area-defined

varieties of Kashmiri are very tentatively classified; and, for most of these,

we do not have any descriptions or lexicons available (see Grierson,1915; and

Kachru, 1969).

The Kashmiri language and its

dialects are spoken by 1,959,115 people in the Valley of Kashmir and surrounding

areas. The language area covers approximately 10,000 square miles in the Jammu

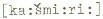

and Kashmir State. [2] The natives of Kashmir call their land  and their language

and their language  .

In Hindi-Urdu the t.mp3s .

In Hindi-Urdu the t.mp3s  or

or  are used for the language.[3]

are used for the language.[3]

The question of the linguistic

origin of Kashmiri, and its relation,on the one hand, to the Dardic group of

languages and, on the other hand to the Indo-Aryan group of languages, continues

to be discussed. The question was originally raised in a serious sense by

Grierson. [4] He claimed that, linguistically, Kashmiri holds a peculiar

position because it has some f.mp3al features which show its Dardic

characteristics and many other features which it shares with the Indo-Aryan

languages. There are basically the following two views on the origin of

Kashmiri. The first view is that Kashmiri developed like other Indo-Aryan

languages, (e.g., Hindi and Punjabi) out of the Indo-European family of

languages and thus, may be considered a branch of Indo-Aryan. Chatterjee argues

that

... Kashmiri, in spite of a Dardic

substratum in it people and its speech, became a part of the Sanskritic

culture-world of India. The Indo-Aryan Prakrits and Apabhramsa from the

Midland and from Northern Panjab profoundly modified the Dardic bases of

Kashmiri, so that one might say that the Kashmiri language is a result of a

very large over-laying of a Dardic base with Indo-Aryan elements. [5]

The second view is that Kashmiri

belongs to a separate group--within the Indo-Aryan branch of

Indo-European--called the Dardic (or the ) group of languages, the other

two members of the group being Indo-Aryan and Iranian. Grierson suggests

that

... the  languages, which include the Shina-Khowar group, occupy a position

int.mp3ediate between the Sanskritic languages of India proper and Eranian

languages farther to their west. They thus possess many features that are

common to them and to the Sanskritic languages. But they also possess features

peculiar to themselves, and others in which they agree rather with languages

of the Eranian family.... That language [Kashmiri] possesses nearly all the

features that are peculiar to

languages, which include the Shina-Khowar group, occupy a position

int.mp3ediate between the Sanskritic languages of India proper and Eranian

languages farther to their west. They thus possess many features that are

common to them and to the Sanskritic languages. But they also possess features

peculiar to themselves, and others in which they agree rather with languages

of the Eranian family.... That language [Kashmiri] possesses nearly all the

features that are peculiar to  ,

and also those in which ,

and also those in which  agrees with Eranian. [6]

agrees with Eranian. [6]

Three language groups are included in

the Dardic family: the Kafiri Group, the Khowar Group, and the Dard

Group. It is rather difficult to give the exact number of speakers of these

three groups because political and geographical factors have made it impossible

to secure any reliable figures. Often the number of speakers and the name

of a language varies from study to study. Traditionally, the above three groups

have further been sub-classified according to the languages and/or dialects in

each group. In three available studies [7], one finds extreme differences and

confusions in both the names and number of languages listed under these three

groups. These lists, according to Morgenstiern [8], are partially correct.

Morgenstiern has also pointed out other inconsistencies pertaining to the names

of languages and/or dialects as they appear in these studies.

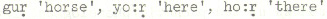

Table Showing the

Speakers of Dardic Languages [9]

| Language (or Group) |

Number of Speakers |

| Kifiri Group |

1 |

| Khowar Group |

3 |

| Shina |

856 |

| Brokpa |

544 |

| Chilasi |

82 |

| Gilgiti |

76 |

| Siraji |

19,978 |

| Bunjwali |

550 |

Out of the languages of the Dardic

Group, Kashmiri came under the direct influence of Sanskrit and later Prakrits,

and much later under Persian and Arabic.

There has been no serious dialect

research on Kashmiri. The outdated and rather tentative dialect classification

of Kashmiri by Grierson continues to be used in current literature. Adopting the

same framework, the dialects of Kashmiri may be grouped along two dimensions:

(a) those dialects which are area-defined, and (b) those dialects which are

defined in t.mp3s of the user.

The list of area-defined dialects

given in Grierson and in the Census of India 1961 are not identical. In

the latter, the following dialects are listed: Bunjwali (550); Kishtwari

(11,633); Poguli (9,508); Shiraji-Kashmiri (19,978); Kaghani (152); and

Kohistani (81). Grierson, on the other hand, claims that Kashmiri has

"only one true dialect--Kashtawari" and "a number of mixed

dialects such as Poguli, Siraji of Doda and Rambani .... Farther east, over the

greater part of the Riasi District of the State, there are more of these mixed

dialects, about which nothing certain is known, except that the mixture is

rather between Kashmiri and the Chibhali f.mp3 of Lahanda." [10]

There has been no

linguistically-oriented field work on the dialects of Kashmiri. The above

classifications, det.mp3ined by both Grierson and the Census of India, 1961, seem

to be arbitrary and subjective. Perhaps further investigation may show that

Kashtawari is the only dialect of Kashmiri,as is claimed by Grierson, and that

the other varieties are (a) those based on the variations of village speech, (b)

those based on Sanskrit and Persian/Arabic influences, and (c) those based on

professions and occupations of speakers. In some studies, the above (b) have

been t.mp3ed the religious dialects of Kashmiri (i.e., Hindu Kashmiri and Muslim

Kashmiri).

In current literature, the

following are generally treated as the area-defined dialects of Kashmiri:

1. Kashtawari :

This is spoken in the Valley of Kashtawar which lies on the southeast of

Kashmir, on the upper Chinab River. It shows the deep influence of the Pahari

and the Lahanda dialects, and is written in the Takri characters.

2. Poguli : This is spoken in the

valleys of Pogul, Paristan and Sar. These valleys lie to the west of Kashtawar

and to the south of the Pir Pantsal (Panchal) range. Bailey has used the

cover-t.mp3 Poguli for the language of this area. It is mixed with the Pahari

and Lahanda dialects.

3. Siraji : This is spoken in the

town of Doda on the River Chinab. Whether or not it is a dialect of Kashmiri

is still debated. Grierson thinks that it can, with almost "equal

correctness, be classed as a dialect of Kashmiri... because it possesses

certain Dardic characteristics which are absent in Western Pahari. [11]

4. Rambani : This is spoken in a small area

that lies between Srinagar and Jammu. It is a mixture of Siraji and Dogri, and

shares features with both Kashmiri and Dogri.

In the literature, the Kashmiri Speech

Community has traditionally been divided into the following area-defined

dialects:

(a) mara:z

(in the southern and southeastern region),

(b) kamra:z (in

the northern and northwestern region), and

(c) yamra:z (in

Srinagar and some of its surrounding areas).

On the basis of this grouping,

it is believed that the Kashmiri spoken in the mara:z

area is highly Sanskritized and the variety spoken in the kamra:z

area has had a deep Dardic influence. Note that further research on the dialect

situation of Kashmiri may show that, in addition to village dialects (and

perhaps religious dialects), Kashtawari is the only dialect of Kashmiri outside

of the valley, and that the other dialects discussed above are only partially

influenced by Kashmiri, since they are spoken in transition zones.

| Sanskritized and

Persianized Dialects |

In earlier and current literature,

it has been claimed that in t.mp3s of the users there are two dialects of

Kashmiri: Hindu Kashmiri, and Muslim Kashmiri [12] The evidence

presented for this religious dichotomy is that Hindu Kashmiri has borrowings

from Sanskrit sources, and Muslim Kashimri has borrowings from Persian (and

Arabic) sources. It turns out that the situation is not as clear cut as has been

presented by Grierson and Zinda Koul 'Masterji', for example. The religious

dichotomy applies, to some extent, to Srinagar Kashmiri, but it presents an

erroneous picture of the overall dialect situation of the language. We shall,

therefore, use rather neutral t.mp3s, i.e., Sanskritized Kashmiri (SK) and

Persianized Kashmiri (PK).

The differences at the

phonetic/phonological levels between the two communities may be explained in

t.mp3s of distribution and frequency of certain phonemes. The sub-system of

borrowed phonological features also is shared by the educated speakers of the

two communities (e.g., /f/ and /q/). The other differences are mainly lexical

and, in a very few cases, morphological. Lexically, SK has borrowed from

Sanskrit sources and PK from Persian and Arabic sources. This aspect of

Kashmiri, however, needs further research.

In village Kashmiri, the

religion-marking phonetic/phonological and morphological features merge into

one, though in Srinagar Kashmiri, as stated earlier, they mark the two

communities as separate. In recent years, with the spread of education, the

religious differences have been slowly disappearing. In earlier studies, the

observations made on the religious dialects of Kashmiri are mainly based on

lexical evidence, and whatever phonetic/phonblogical evidence is presented

is from Srinagar Kashmiri. Consider, for example, the sound alternations in the

following section.

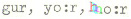

Pronunciation

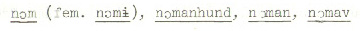

The following variations are,

essentially, the substitution of different phonemes in individual lexical items.

It seems that the two communities share one overall phonological system; In

Srinagar Kashmiri  alternates with [r] in the speech of Muslims. This feature is again shared by

both communities in village Kashmiri, (e.g., PK

alternates with [r] in the speech of Muslims. This feature is again shared by

both communities in village Kashmiri, (e.g., PK  ;

SK ;

SK  ).

Note also, among others, the following differences: ).

Note also, among others, the following differences:

VOWELS

CONSONANTS

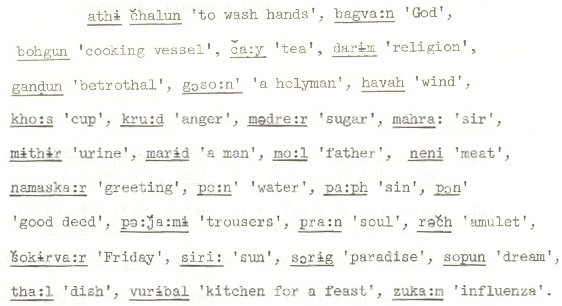

Lexis

The lexical variation between SK and

PK is based on the sources of lexical items. In SK there is a high frequency of

Sanskrit items, while in PK there are Persian and Arabic borrowings. On the

other hand, a number of registers (e.g., legal or business) have a high

frequency of Persio-Arabic borrowings that are shared by both the communities.

Note that the dichotomy of SK and PK does not always hold with reference to the

use of Sanskritized words by the Hindus and Persianized words by the Muslims.

There are several examples where Muslims use SK and Hindus use PK, for example,  'moon' has a high frequency among Muslims. Consider the following two sets of

lexical items.

'moon' has a high frequency among Muslims. Consider the following two sets of

lexical items.

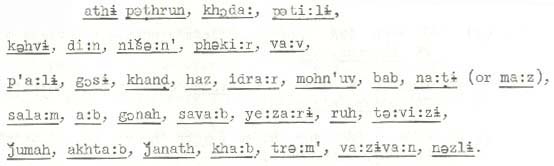

Sanskritized:

The Persianized f.mp3s of these are

given below.

Persianized:

Morphology

The morphological differences are of

two types: those which differ in the source (see above), and those which show

the presence of an item in one community which is now absent in the speech of

the other community.

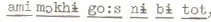

Note, for example, that in PK

hargah has been preserved as a conjunction, but in SK it is fast disappearing, at least

in Srinagar SK. In Srinagar agar

has been preserved as a conjunction, but in SK it is fast disappearing, at least

in Srinagar SK. In Srinagar agar is used more frequently (this is a loan from Hindi-Urdu, Punjabi). This also

applies to the item

is used more frequently (this is a loan from Hindi-Urdu, Punjabi). This also

applies to the item  (e.g.,

(e.g.,  ,

'I did not go there for this reason.') which is restricted to PK. The use of the

following declensions is also restricted to Muslims in Srinagar Kashmiri,

although it is shared by both communities in the villages: ,

'I did not go there for this reason.') which is restricted to PK. The use of the

following declensions is also restricted to Muslims in Srinagar Kashmiri,

although it is shared by both communities in the villages:

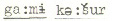

It is customary to consider

Kashmiri, as spoken in Srinagar, as the standard f.mp3 of the language. The

attitude-denoting such t.mp3s as  'village Kashmiri' and

'village Kashmiri' and  'city Kashmiri' are frequently used to mark speakers. The administrative

and educational uses of Kashmiri are still very restricted. Therefore, the

process of standardization is very slow. In recent years, especially since 1947,

Kashmiri has been used for various f.mp3s of creative writing. This has helped in

developing various literary styles.

'city Kashmiri' are frequently used to mark speakers. The administrative

and educational uses of Kashmiri are still very restricted. Therefore, the

process of standardization is very slow. In recent years, especially since 1947,

Kashmiri has been used for various f.mp3s of creative writing. This has helped in

developing various literary styles.

| The Writing

Systems of Kashmiri |

The aim of this manual is not to

introduce a learner to the writing system of Kashmiri. We have, therefore, used

a modified version of the Roman script, with some diacritical marks added. There

were several reasons for this decision. The main reason is that there is

no unif.mp3ity in the use of scripts for Kashmiri. In recent years, Kashmiri has

been written in more than one script. The reasons for this lack of unif.mp3ity

are both socio-religious and political. The following scripts are used for

Kashmiri and some of its dialects.

Developed around the 10th century,

this is the oldest script known to Kashmiris. It is now used for restricted

purposes by a small group among the Kashmiri Pandit community (e.g., for

religious purposes or horoscope writing). In formation, the symbols are

different from the Devanagari symbols and every letter of the alphabet has a

name.

This was used by Kashmiri Hindus

for writing Kashmiri literature until 1947, and is still in use today. It was

made popular particularly by Zinda Koul 'Masterji' and S. K. Toshkhani.

This cuts across religious

boundaries and is now used by both the Pandits and the Muslims. It has also been

recognized as the official script for Kashmiri by the Jammu and Kashmir

government.

This, too, has been used by a very

small number of Kashmiris (see J. L. Kaul, Kashmiri Lyrics).

This is used in the Kashtawar area

for Kashtawari.

In the Dardic group, Kashmiri is

the only language which has a literary tradition. The earliest literary text of

Kashmiri has been placed between 1200 and 1500 A.D. The tradition of literary

writing, however, was not continuous, and there have been many significant

interruptions. We may divide the history of Kashmiri literature, on the basis of

the language features and content of the texts, into the following tentative

periods: the Early Period (up to 1500 A.D.), the Early Middle Period (1500 to

1800 A.D.), the Late Middle Period (up to 1900 A.D.), the Modern Period

(1900-1946), the Contemporary Period (1947- ).

Mahanaya-Prakasha,

a work on Tantric worship, is considered to be the first extant

manuscript written in the Sharda script (cf. 5.0.). Little is known about its

author Sitikanta Acharya. Grierson assigns it to the 15th century, but Chatterji

and some other scholars [13] are of the opinion that it was composed around the

13th century. Another work, Chumma-Sampradaya, is comprised of

seventy-four verses belongs to the same period. The development of prose f.mp3s

of literature (e.g., novels, short stories, drama) is very recent in Kashmiri.

In this book we have written brief notes on five poets of Kashmiri. These

include two poetesses, Lal Ded and Habba

Khatun, and three poets, Zinda Koul 'Masterji',

Gulam Ahmad 'Mahjoor', and Dina

Nath 'Nadim'. We have also included some of their poems (see Lessons

46 through 50).

In general, the languages of the

Dardic-group show a large number of lexical items which have been preserved from

Vedic Sanskrit and which are rarely found in other Indian languages. The

Kashmiri language and literature had two major influences. First, the earliest

phase of Kashmiri shows the impact of Sanskrit on Kashmiri. The second phase

began after the invasions of the Muslims and the large scale conversion to

Islam. This phase led to Persian (and Arabic) influences. The impact of the West

on Kashmiri literature is recent.

in Kashmir

in Kashmir |

In the current language planning of

Kashmir,  does not play an importatnt role. Kashmir is the only State of India in which a

non-native language was introduced as the state language after the Independence.

Thus, Kashmiri, which is the first language of 1,959,115 speakers, is not now in

the language planning of the state. Though Kashmiri is the medium of instruction

in the primary schools, the teachers have inadequate teaching materials and no

motivation for teaching their own language. In this connection, the following

observation continues to be true (see Kachru, 1969).

does not play an importatnt role. Kashmir is the only State of India in which a

non-native language was introduced as the state language after the Independence.

Thus, Kashmiri, which is the first language of 1,959,115 speakers, is not now in

the language planning of the state. Though Kashmiri is the medium of instruction

in the primary schools, the teachers have inadequate teaching materials and no

motivation for teaching their own language. In this connection, the following

observation continues to be true (see Kachru, 1969).

The University of Jammu and Kashmir

has so far shown no interest in research in Kashmiri and/or other Dardic

languages. One can count many reasons for this attitude (e.g., political,

educational), but the main reason is the language-attitude of Kashmiris toward

their own language. This attitude has developed over hundreds of years under

varied foreign political and cultural domination and, in spite of the recent

cultural upsurge, the attitude toward the language has not changed. Perhaps this

is why the Government and other educational institutions [14] do not seriously

consider  under

their academic domain. under

their academic domain.

1.

Braj B. Kachru, "Kashmiri and Other Dardic Languages" in Current

Trends in Linguistics, Vol. 5, ed. Thomas A. Sebeok (The Hague: Mouton ,

1969), p. 284.

2.

Registrar-General and Census Commissioner of India, Census of India,

Vol. 1, Part 2, Language Tables (Delhi: 1965).

3.

In English a number of spellings have been used in literature for

transliterating the word Kashmiri, e.g., Kaschemiri, Cashmiri, Cashmeeree,

Kacmiri.

4.

For arguments in favor and against these two views, cf. G.A. Grierson, The

Linguistic Survey of India, Vol. 8, Part 2, p. 235 and pp. 241-253;

Sunitikumar Chatterji, Indo-Aryan and Hindi, 2nd edition (Calcutta:

1960), pp. 130-131; Languages and Literatures of Modern India

(Calcutta: 1963, pp. 33-34; M.S. Namus, “Origin of Shina Language" in Pakistani

Linguistics 1962, Lahore, pp. 55-60; Census of India 1961, pp. ccii-cciii;

Braj B. Kachru, op. cit.

5.

Sunitikamar Chatterji, Languages and Literatures of Modern India

(Calcutta: 1963)., p. 256.

6.

G.A. Grierson, "The Linguistic Classification of Kashmiri", Indian

Antiquary, XLIV, (1915).

7.

For sub-classifications of languages/dialects under these three groups see:

"The Dardic branch or sub-branch of Indo-European" in the supplement

"Languages of the World: Indo-European Fascicle One" of Anthropological

Linguistics, Vol. 7, No. 8, Nov. 1965, pp. 284-294; Grierson, G.A., Linguistic

Survey of India,Vol. 8, Part 2, p. 2; A. Mitra, Census of India,

1961, Vol. 1, an introductory note on classification by R.C. Nigam, Registrar

General, India, (Delhi: 1964), pp. ccii, cciii, ccxxxiv, 216, and 401. The

following review article based on the available published literature, presents

the same sub-classification as given in the above studies: Braj B. Kachru,

"Kashmiri and Other Dardic Languages", in Current Trends in

Linguistics, Vol. 5, pp. 284-306. It seems that if Morgenstiern's

observation is correct, then all the above mentioned studies are misleading.

Kachru (op. cit.) has referred to this confusion in the

available literature on the Dardic languages in his study. Note the following:

"We do not have reliable figures even about the number of speakers of

these languages. What is worse, in the available studies, there is no

unif.mp3ity about the number and names of languages which are included under

the Dardic group . (Ibid.,p. 286)

The following are some of the

important studies on the Dardic group of languages (mainly on the Kafiri and

Khowar).

S.A. Burnes "On the Siah-Posh

Kafirs: with Specimens of their language and costume" , Journal of the

Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. 7, (1838); G. Morgenstierne,

"Indo-European K in Kafiri", NTS, Vol. 13 (1945);

"The Personal Pronouns first and second plural in the Dardic and Kafir

Languages", IL, Vol. V (1953); Ernest Trumpp, "On the

Language of the So-called Kafirs of the Indian Caucasus", JRAS,

Vol. 29 (1862), (also cf. ZDMG, Vol. 20, 1868).

G. Morgenstierne, "Some

Features of Khowar Morphology", NTS, Vol 24 (1947); "Sanskrit

Words in Khowar", in Felicitation Volume Presented to Professor Sripad

Krishna Belvalkar , ed. S. Radhakrishnan, et. al. (Benaras: 1957); D.J.T.

O'Brien, Grammar and Vocabulary of the Khowar Dialect (Chitrali), with

Introductory Sketch of country and People (Lahore: 1895).

See also footnote 9 for Shina.

8.

In a personal communication dated June 1, 1970, Georg Morgenstierne, makes the

following points about the classification of the Dardic group of languages:

a) Wai-ala is

identical with Waigali of which Zhonjigali is a sub-dialect;

b) Prasun is another name for Wasi-veri;

c) the correct f.mp3 [of Ashkund] is

Ashkun;

d) Dameli [not mentioned in any of the

lists in above mentioned studies (see fn. 7)] "might possibly be

included" among the languages in the Kafir group;

e) "Gowar-bati, Pashai and Tirahi

are not Kafir languages, and Lagman, Deghani (for Dehgani) are neither

alternative names for Pashai as a whole, nor well-chosen names for the most

important dialects of this extremely split-up language";

f) Bashkarik belongs (together with

Torwali and other dialects) to the Kohistani group, "at any rate in the

generally accepted meaning of this t.mp3";

g) Gujuri is not a Kafiri nor even a

Dardic language; under Shina the archaic Phalura (in Chitral) should be

mentioned.

In addition to this he has also

made certain points about the Khowar group. This communication of

Morgenstierne makes it clearer that we still do not have even a definitive or

reliable classification of these languages. The three studies mentioned in fn.

7 are therefore to be taken as very tentative and in many cases misleading and

incorrect.

9.

Cf. The Census of India, 1961 (Delhi: 1964), pp. ccii-cciii. Note that

the Census Report makes it clear that "...the Kafir and Khowar groups of

speakers have their main concentration outside the Indian territory ...".

10. The

Linguistic Survey of India, Vol. 8, Part 2, p. 233.

11.

Ibid., p. 433.

12.

Braj B. Kachru, op. cit.

13.

Sunitikumar Chatterji, Languages and Literatures of Modern India

(Calcutta: 1963), pp. 258-259.

14.

Kachru, op. cit., p. 300.

|